This post was originally written as the text for a talk I gave at a British Library Lab's event in London in early November 2014. In the nature of these things, the rhythms of speech and the verbal ticks of public speaking remain in the prose. It has been lightly edited, but the point remains the same.

In recent months there has been a lot of talk about big stuff. Between 'Big Data' and calls for a return to ‘Longue durée’ history writing, lots of people seem to be trying to carve out their own small bit of 'big data'. This post represents a reflection on what feels to me to be an important emerging strategy for information interrogation driven by the arrival of 'big data' (a 'macroscope'); and a tentative step beyond that, to ask what is lost by focusing exclusively on the very large.

And the place I need to start is with the emergence of what feels to me like an increasingly commonplace label – a ‘macroscope’ - for a core aspiration of a lot of people working in the Digital Humanities.

As far as I can tell, the term ‘macroscope’ was coined in 1969 by Piers Jacob, and used as the title of his science fiction/fantasy work of the same year – in which the ‘macroscope’, a large crystal, able to focus on any location in space-time with profound clarity, is used to produce something like a telescope of infinite resolution. In other words, a way of viewing the world that encompasses both the minuscule, and the massive. The term was also taken up by Joel de Rosnay and deployed as the title of a provocative book on systems analysis first published in 1979. The label has also had a long and undistinguished afterlife as the trademark for a suite of project management tools – a ‘methodology suite’ - supported by the Fujistu Corporation.

But I think the starting point for interest in the possibility of creating a ‘macroscope’ for the Digital Humanities, comes out of computer science, and the work of Katy Börner from around 2011.

Her designs and advocacy for the development of a ‘Plug and Play Macroscope’, seems to have popularised the idea to a wider group of Digital Humanists and developers. To quote Börner:

'Macroscopes provide a "vision of the whole," helping us "synthesize" the related elements and detect patterns, trends, and outliers while granting access to myriad details. Rather than make things larger or smaller, macroscopes let us observe what is at once too great, slow, or complex for the human eye and mind to notice and comprehend.' (Katy Börner, ‘Plug-and-Play Macroscopes’, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 54 No. 3, Pages 60-6910.1145/1897852.1897871)

In other words, for Börner, a macroscope is a visualisation tool that allows a single data point, to be both visualised at scale in the context of a billion other data points, and drilled down to its smallest compass.

This was not a vision or project initially developed in the humanities. Instead it was a response to the conundrums of ‘Big Data’ in both STEM academic disciplines, and the wider commercial world of information management. But more recently, a series of ‘macroscope’ projects have begun to emerge from within the humanities, tied to their own intellectual agendas, and subtly recreating the idea with a series of distinct emphases.

Perhaps the project most heavily promoted recently, is Paper Machines, created by Jo Guldi and Chris Johnson-Robertson – and the MetLab at Harvard. This forms a series of visualisation tools, built to work with Zotero, and ideally allowing the user to both curate a large scale collection of works, and explore its characteristics through space, time and word usage. In other words, it is designed to allow you to build your own Google Books, and explore.

There are problems with Paper Machines, and most people I know have struggled to make it work consistently. But it rather nicely builds on the back of functionality made available through Zotero, and effectively illustrates what might be described as a tool for ‘distant reading’ that encompasses elements of a ‘macroscope’.

What is most interesting about it, however, is the use its creators make of it in seeking to shift a wider humanist discussion from one scale of enquiry to another.

Last month, to great fanfare, CUP published Jo Guldi and David Armitage’s History Manifesto, which argues that once armed with a ‘macroscrope’ – Paper Machines in their estimation – historians should pursue an analysis of how ‘big data’ might be used to re-negotiate the role of the historian – and the humanities more generally.

Basically, what Guldi and Armitage are calling for through both the Manifesto and through Paper Machines, is the re-invention of ‘Longue durée’ history – telling ever larger narratives about grand sweeps of historical change, encompassing millennia of human experience. And to do this in pursuit of taking on the mantle of a public intellectual, able to speak with greater authority to ‘power’.

In the process they explicitly denigrate notions of ‘micro-history’ as essentially irrelevant. At one and the same time, they seem to me to celebrate the possibility of creating a ‘macroscope’, while abjuring half its purpose.

What we see in this particular version of a ‘macroscope’ is a tool that privileges only one setting on the scale between a single data point, and the sum of the largest data set we can encompass. In other words, by seeking the biggest of big stories, it is missing the rest.

Perhaps the other most eloquent advocate for a ‘macroscope’ at the minute is Scott Weingart. With Shawn Graham and Ian Milligan, he is writing a collective online ‘book’ entitled, Big Digital History: Exploring Big Data through a Historian’s Macroscope. The book is a nice run through of digital humanist tools, but the important text from my perspective is a blog post Weingart published on the 14 September 2014. The post was called: The moral role of DH in a data-driven world; and in it, Weingart advocates a very specific vision of a ‘macroscope’, in which the largest scale of reference and view is made intelligible through the application of a formal version of network analysis.

Weingart is a convincing advocate for network analysis, performed in light of some serious and sophisticated automated measures of distance and direction. And his work is a long way ahead of much of the naïve and unconvincing use of network visualisations current in large parts of the Digital Humanities. Weingart also makes a powerful case for where a limited number of DH tools – primarily network analysis and topic modelling - could be deployed in re-engaging the ‘humanities’ with a broader social discussion.

Again, like Guldi and Armitage, Weingart seeks in 'Big Data' a means through which the Humanities can ‘speak to power’.

As with the work of Armitage and Guldi, the pressing need to turn Digital Humanities to political account appears to motivate a search for large scale results that can be deployed in competition with the powerful voices of a positivist STEM tradition. My sense is that Weingart, Armitage and Guldi are all essentially scanning the current range of digital tools, and selectively emphasising those that feel familiar from the more ‘Social Science’ end of the Humanities. And that having located a few of them, they are advocating we adopt them in order to secure our place at the table.

In other words, there is a cultural/political negotiation going on in these developments and projects that is driven by a laudable desire for ‘relevance’, but which effectively moves the Humanities in the direction of a more formal variety of Social Science.

Others still, are arguably doing some of the same work, but using a different language, or at the least seeking a different kind of audience.

Jerome Dobson, for example, has recently begun to describe the use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in historical geography, as a form of ‘macroscope’. This usage doesn’t come freighted with the same political claims as are current in Digital Humanities, but seem to me an entirely reasonable way of highlighting some of the global ambitions – and sensitivity to scale - that are inherent in GIS. The notion - perhaps fostered most fully by Google Earth - that you can both see the world in its entirety, as well as zoom in to the smallest detail, seems at one with a data driven ‘macroscope’. But, again, the scale most geographers want to work with is large – patterns derived from billions of data points. And again, the siren call of GIS, tends to pull humanist enquiry towards a specific form of social science.

And finally, we might also think of the approach exemplified in the work of Ben Schmidt as another example of a ‘macroscope’ approach – particularly his ‘prochronism’ projects. These take individual words in modern cinema and television scripts that purport to represent past events – things like Downton Abbey and Mad Men - and compares them to every word published in the year they are meant to represent.

Building on Google Books and Google Ngrams, Schmidt is effectively mixing scales of analysis at the extremes of ‘big data’, on the one hand – all words published in a single year – and small data, on the other.

Of all the examples mentioned so far, it is only Schmidt who is actually using the functionality of a ‘macroscope’ effectively, making it all the more ironic that he doesn’t adopt the term.

And almost uniquely in the Digital Humanities – a field equally remarkable for its febrile excitement, and lack of demonstrable results – Schmidt’s results have been starkly revealing. My favourite example, is his analysis of the scripts of Mad Men, which illustrates that early episodes referencing the 1950s, overuse language associated with the ‘performance’ of masculinity – words that reflect ‘behaviour’. And that later episodes, located in the 1970s, overuse words reflecting the internalised emotional experience of masculinity. For me this revealed beautifully the larger narrative arc of the programme in a way that had not been obvious prior to his work.

Schmidt has little of the wider agenda to influence policy and politics evident in that of Armitage, Guldi and Weingart, but ironically, it is his work that is having some of the greatest extra-academic impact, via the anxiety it has created in the script writers of the shows he analyses.

All of which is simply to say that playing with and implementing ideas around a ’macroscope’ is quite popular at the moment. And a direction of travel which, with caveats, I wholly support.

But it also leaves me in something of a conundrum.

Each of these initiatives, with the possible exception of Schmidt’s work, seems to locate themselves somewhere other than the Humanities I am familiar with. And this seems odd. Issues of scale are central to this. Claiming to be doing ‘big history’ sounds exciting; while claiming that more formal ‘network analysis’, will answer the questions of a humanist enquiry, appears to create a bridge between disciplines – allowing Humanists and more data driven parts of the Social Sciences to share a methodology and a conversation. But with the exception of Schmidt’s work, these endeavours seem to be privileging particular types of analysis – Social Science types of analysis – over more traditionally Humanist ones.

In some ways, this is fine. I have discovered to my own benefit, that working with ‘Big Data’ at scale and sharing methodologies with other disciplines is both hugely productive, and hugely fun. To the extent that ‘big stories’ and new methodologies provide the justification for collaborating with researchers from a variety of disciplines – statisticians, mathematicians and computer scientists – they are wholly positive, and a simple ‘good thing’.

And yet… I find myself feeling that in the rush to define how we use a ‘macroscope’, we are losing touch with what humanist scholars have traditionally done best.

I end up is feeling that in the rush to new tools and ‘Big Data’ Humanist scholars are forgetting what they spent much of the second half of the twentieth century discovering – that language and art, cultural construction, human experience, and representation are hugely complex – but can be made to yield remarkable insight through close analysis. In other words, while the Humanities and ‘Big Data’ absolutely need to have a conversation; the subject of that conversation needs to change, and to encompass close reading and small data.

The Stanford Humanities Centre defines the ‘Humanities’ as:

'…the study of how people process and document the human experience. Since humans have been able, we have used philosophy, literature, religion, art, music, history and language to understand and record our world.'

Which makes the Humanities sound like the most un-exciting, ill-defined, unsalted, intellectual porridge ever. And yet, when I think about the scholarly works that have shaped my life, there is none of this intellectual cream of wheat.

Instead, there are a series of brilliant analyses that build from beautifully observed detail at the smallest of scales.

I look back to the British Marxist tradition in history – to Raphael Samuel and Edward Thompson – and what I see are closely described lives, built from fragments and details, made emotionally compelling by being woven into ever more precise fabrics of explanation.

A gesture, a phrase, a word, an aching back, a distinctive tattoo. 'My dearest …. Remember when…'

The real power of work in this tradition, lay in its ability to deploy emotive and powerful detail in the context of the largest of political and economic stories. And the political project that underpinned it, was not to ‘speak to power’, but to mobilise the powerless, and democratise identity and belonging. With Thompson’s liquid prose, a single poor, long dead framework knitter affected more change than any amount of more formal economic history.

Or I think of the work of Pierre Bourdieau, Arlette Farge and de Certeau, and the ways in which they again use the tiny fragments of everyday life - the narratives of everyday experience - to build a compelling framework illustrating the currents and sub-structures of power.

Or I think of Michel Foucault, who was able to turn on its head every phrase and telling line – to let us see patterns in language – discourses – that controlled our thoughts. Foucault profoundly challenged us to escape the limits of the very technologies of communication and analysis we used; and to see in every language act, every phrase and word, something of politics.

By locating the use of a ‘macroscope’ at the larger scale, seeking the Longue durée, and the ear of policy makers, recent calls for how we choose to deploy the tools of the Digital Humanities appear to deny the most powerful politics of the Humanities. If today we have a public dialogue that gives voice to the traditionally excluded and silenced – women, and minorities of ethnicity, belief and dis/ability – it is in no small part because we now have beautiful histories of small things. In other words, it has been the close and narrow reading of human experience that has done most to give voice to people excluded from ‘power’ by class, gender and race.

Besides simply reflecting a powerful form of analysis, when I return to those older scholarly projects I also see the yearning for a kind of ‘macroscope’. Each of these writers strive to locate the minuscule in the massive; the smallest gesture in its largest context; to encompass the peculiar and eccentric in the average and statistically significant.

What I don’t see in modern macroscope projects is a recognition of the power of the particular; or as William Blake would have it:

To see a World in a grain of sand,

And a Heaven in a wild flower...

Auguries of Innocence (1803, 1863).

Current iterations of the idea of a macroscope, with all their flashy, shock and awe visualisations, probably score over these older technologies of knowing in their sure grasp of data at scale, but in the process they seem to lose the ability to refocus effectively.

For all the promise of balancing large and small scales, the smaller and particular seem to have been ignored.

Ever since the Apollo 17 sent back its pictures of earth as a distant blue marble, our urge towards the all-inclusive, global and universal has been irresistible. I guess my worry is that in the process we are losing the ability to use fine detail in the ways that make the work of Thompson and Bourdieau, Foucault and Samuel, so compelling.

So, by way of wending towards some kind of inconclusive conclusion. I just want to suggest that if we are to use the tools of 'Big Data' to capture a global image, it needs to be balanced with the view from the other end of the macroscope (along with every point in between).

In part this is just about having self-confidence as humanist scholars, and ironically serving a specific role in the process of knowing, that people in STEM are frequently not very good at.

Several recent projects I was privileged to participate in, involved some hugely fun work with mathematicians and information scientists exploring the changing linguistic patterns found in the Old Bailey trials – all 127 million words worth. And after a couple of years of working closely with a bunch of brilliant people, what I gradually realised was that while mathematicians do a lot of ‘close reading’ – of formulae and algorithms - like most scientists, they are less interested than I am in the close reading of a single datum.

In STEM cleaning data is a chore. Geneticists don’t read the human genome base by base; and our knowledge of the Higgs Boson is built on a probability only discovered after a million rolls of the dice, with no one really looking too carefully at any single one.

In many respects ‘big data’ actually reinforces this tendency, as the assumption is that the ‘signal’ will come through, despite the noise created by outliers and weirdness. In other words, ‘Big Data’ supposedly lets you get away with dirty data. In contrast, humanists do read the data; and do so with a sharp eye for its individual rhythms and peculiarities – its weirdness.

In the rush towards 'Big Data' – the Longue durée, and automated network analysis; towards a vision of Humanist scholarship in which Bayesian probability is as significant as biblical allusion, the most urgent need seems to me to be to find the tools that allow us to do the job of close reading of all the small data that goes to make the bigger variety.

This is not a call to return to some mythical golden age of the lone scholar in the dusty archive – going gradually blind in pursuit of the banal. This is not about ignoring the digital; but a call to remember the importance of the digital tools that allow us to think small; at the same time as we are generating tools to imagine big.

In relation to text, you would think this is easy enough. Easy enough to, like Ben Schmidt, test each word against its chronological bed-fellows; or measure its distance from an average for its genre.

When I am reading a freighted phrase from the 1770s, like ‘pursuit of happiness’, I want to know that till then, ‘happiness’ was almost exclusively used in a religious context – ‘Eternal Happiness’ - and that its use in a secular setting would have caught in a reader’s mind as odd and different - new. We should be able to mark the moment when Thomas Jefferson allowed a single word to escape from one ‘discourse’ and enter another – to read that word in all its individual complexity, while seeing it both close and far.

I know of no work designed to define the content of a ‘discourse’, and map it back in to inherited texts. I know of no projects designed with this notion in mind. And if you want a take home a message from this post, it is a simple call for ‘radical contextualisation’.

To do justice to the aspirations of a macroscope, and to use it to perform the Humanities effectively – and politically – we need to be able to contextualise every single word in a representation of every word, ever. Every gesture contextualised in the collective record all gestures; and every brushstroke, in the collective knowledge of every painting.

Where is the tool and data set that lets you see how a single stroll along a boulevard, compares to all the other weary footsteps? And compares it in turn to all the text created along that path, or connected to that foot through nerve and brain and consciousness. Where is the tool and project that contextualises our experience of each point on the map, every brush stroke, and museum object?

This is not just about doing the same old thing – of trying to outdo Thompson as a stylist, or Foucault for sheer cultural shock. My favourite tiny fragment of meaning – the kind of thing I want to find a context for - comes out of Linguistics. It is new to me, and seems a powerful thing: Voice Onset Timing – that breathy gap between when you open your mouth to speak, and when the first sibilant emerges. This apparently changes depending on who are speaking to – a figure of authority, a friend, a lover. It is as if the gestures of everyday life can also be seen as encoded in the lightest breathe. Different VOTs mark racial and gender interactions, insider talk, and public talk.

In other words, in just a couple of milliseconds of empty space there is a new form of close reading that demands radical contextualisation (I am grateful to Norma Mendoza-Denton for introducing me to VOT).

And the same kind of thing could be extended to almost anything. The mark left by a chisel is certainly, by definition, unique, but it is also freighted with information about the tool that made it, the wood and the forest from which it emerged; the stroke, the weather on the day, and the craftsman.

One of the great ironies of the moment is that in the rush to big data – in the rush to encompass the largest scale, we are excluding 99% of the data that is there. And if we are going to build a few macroscopes, I just want to suggest that, along with the blue marble views, we keep hold of the smallest details.

And if we do so, looking ever more closely at the data itself – remembering that close reading can be hugely powerful - Humanists will have something to bring to the table, something they do better than any other discipline. They can provide a world of ‘small data’ and more importantly, of meaning, to balance out the global and the universal – to provide counterpoint in the particular, to the ever more banal world of the average.

This blog is a space for me to rant in that most seventeenth-century sense of the word; and to cut and paste the ideas and comments that don't seem to fit in more traditional forms of academic publication.

Showing posts with label positivism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label positivism. Show all posts

Sunday, 9 November 2014

Monday, 9 December 2013

Big Data for Dead People: Digital Readings and the Conundrums of Positivism

The following post is drawn from the text of a keynote talk I delivered at the CVCE conference on 'Reading Historical Sources in the Digital Age', held in Luxembourg on the 4th and 5th of December 2013. In the nature of these kinds of texts the writing is designedly rough, the proof reading rudimentary, and the academic apparatus largely absent.

This talk forms a quiet reflection on how the creation of new digital resources has changed the ways in which we read the past; and an attempt to worry at the substantial impact it is having on the project of the humanities and history more broadly. In the process it asks if the collapse of the boundaries between types of data - inherent in the creation of digital simulcra - is not also challenging us to rethink the 'humanities' and all the sub-disciplines of which it is comprised. I really just want to ask, if new readings have resulted in new thinking? And if so, whether that new thinking is of the sort we actually want?

As Lewis Mumford suggested some fifty years ago, most of the time:

‘… minds unduly fascinated by computers carefully confine themselves to asking only the kind of question that computers can answer...’

Lewis Mumford, “The Sky Line "Mother Jacobs Home Remedies",” The New Yorker, December 1, 1962, p. 148.

But, it seems to me that we can do better than that, but that in the process we need to think a bit harder than we have about the nature of the Digital History project.

Perhaps the obvious starting point is with the concept of the distant reading of text, and that wonderful sense that millions of words can be consumed in a single gulp. Emerging largely from literary studies, and in the work of Franco Moretti and Stephen Ramsay, the sense that text – or at least literature – can be usefully re-read with the tools of the digital humanities has been regularly re-stated with the all the hyperbole for which the Digital Humanities is so well known. And, within reason, that hyperbole is justified.

My favourite example of this approach is Ben Schmidt’s analysis of the dialogue in Mad Men, in which he compares the language deployed by the scriptwriters against the corpus of text published in that particular year drawn from Google books. In the process he illustrates that early episodes over-state the ‘performative’ character of the language, particularly in relation to masculinity – that the scriptwriters chose to depict male characters talking about the outside world and objects, more frequently than did the writers of the early fifties. And that in the later episodes of the series, they depict male characters over-using words associated with interiority, emotions and personal perceptions. What I like about this is that it forms one of the first times I have been really surprised by ‘distant reading’. I just had not clocked that the series was developing a theme along these lines – that it embedded a story of the evolution of masculinity from a performative to an interiorised variety. But once Schmidt used a form of distant reading to expose the transition it felt right, obvious and insightful. In Schmidt’s words: ‘the show's departures from the past… let us see just how much everything has changed, even more than its successes.’… at mimicking past language. The same could be done with the works of George Elliot or Tolstoy (who both wrote essentially ‘historical’ novels), and with them too, I look forward to being surprised. In other words, the existence of something like Google Books and the Ngram viewer - which Schmidt's work depends upon - actually can change the character of how we ‘read’ a sentence, a word, a phrase, a genre – by giving a norm against which to compare it. Is it a ‘normal’ word, for the date? or more challenging, for the genre? for the place of publication? for the word's place in the long string of words that make up an article or a book?

But having lauded this example, I think we also have to admit that in most stabs at distant reading seems to tell us what we already know.

There was an industrial revolution involving iron. There was a war in the 1860s and so on.

What surprises me most, is that I am not more surprised.

In part, I suspect the banal character of most ngrams and network analyses is a reflection of the extent to which books, indexes, and text, have themselves been a very effective technology for thinking about words. And that as long as we are using digital technology to re-examine text, we are going to have a hard time competing with two hundred years of library science, and humanist enquiry. Our questions are still largely determined by the technology of books and library science, so it is little wonder that our answers look like those found through an older techonology.

But, the further we move away from either the narrow literary cannon; and more importantly the code that is text, to include other types of readings of other types of data - sound, objects, spaces - I hope the more unusual and surprising our readings – both close and distant - might become. And it is not just text and objects, but also cultures. The current collection of digital material that forms the basis for most of our research is composed of the maudlin leavings of rich dead white men (and some rich dead white women). Until we get around to including the non-cannonical, the non-Western, the non-textual and the non-elite, we are unlikely to be very surprised.

For myself, I am wondering how we might relate non-text to text more effectively; and how we might combine - for historical purposes - close and distant reading into a single intellectual practise; how we might identify new objects of study, rather than applying new methodologies to the same old bunch of stuff. And just by way of a personal starting point, I want to introduce Sarah Durrant. She is not important. Her experience does not change anything, but she does provide a slightly different starting point from all the rich dead white men. And for me, she represents a different way of thinking through how to ask questions of computers, without simply asking questions we know computers can answer.

Sarah claimed to have found two bank notes on the floor of the coffee house she ran in the London Road, on the Whitsun Tuesday, 1871; at which point she pocketed them. In fact they had been lifted from the briefcase of Sydney Tomlin, in the entrance way of the Birkbeck Bank, Chancery Lane, a few days earlier.

We know what Sarah looked like. This image is part of the record of her imprisonment at Wandsworth Gaol for two years at hard labour, and is readily available through the website of the UK's National Archives. We have her image, her details, her widowed status, the existence of two moles - one on her nose and the other on her chin. We have her scared and resentful eyes staring at us from a mug shot. I don't have the skill to interpret this representation in the context of the history of portraiture, or the history of photography - but it creates a powerful if under-theorised alternative starting point from which to read text - and has the great advantage of not being ‘text’; or at least not being words.

But, we also have the words recorded in her trial.

And because we have marked up this material to within an inch of their life in XML to create layer upon layer of associated data, we also have something more.

In other words, for Sarah, we can locate her words, and her image, her imprisonment and experience, both in ‘text’ and in the leavings of the administration of a trial, as marked up in the XML. And because we have studiously been giving this stuff away for a decade, there is a further ‘reading’ that is possible, via an additional layer of XML provided by Magnus Huber and his team at the University of Giessen. He has marked up all the text that purports to encompass a ‘speech act’. And so we also have a further ‘reading’ of Sarah as a speaker, and not just any speaker, but a working class female speaker in her 60s.

And of course, this allows us to compare what she says, to other women of the same age and class, using the same words; with a bit of context for the usage.

So, we already have a few ‘readings’, including text, bureaucratic process, and purported speech.

From all of which we know that Sarah, moles and all, was convicted of receiving; and that she had been turned in by a Mrs Seyfert - a drunk, who Durrant had refused a hand-out. And we know that she thought of her days in relation to the Anglican calendar, which by 1871, was becoming less and less usual – and reflects the language of her childhood.

And, of course, we have an image of the original page on which that report was published – a ghost of the material leavings of an administrative process.

And just in case, we can also read the newspaper report of the same trial.

So far, so much text, with a couple of layers of XML, and the odd image. But we also know who was in Wandsworth Gaol with her on the census day in 1871.

And we know where Durrant had been living when the crime took place – in Southwark, at No 1 London Road.

We know that she was a little uncertain about her age, and we know who lived up one flight of stairs, and down another. Almost randomly, we can now know an awful lot about most nineteenth century Londoners, allowing us to undertake a new kind of 'close reading'.

From which it is a small step to The Booth Archive site posted by the London School of Economics, which in turn lets us know a bit more about the street and its residents.

‘a busy shopping street', with the social class of the residents declining sharply to the West - coded Red for lower middle class.

But we can still do a bit better than this. We can also do what linguists and literary scholars are doing to their own objects of study - we can take apart the trial, for instance, as a form of generic text using facilities such as Voyant Tools. Turning a ‘historical reading’ in to a linguistic one:

And, if the OCR of the Times Digital Archive was sufficiently good (which it isn’t) - we could have compared the trial account, with the newspaper account as a measurable body of text.

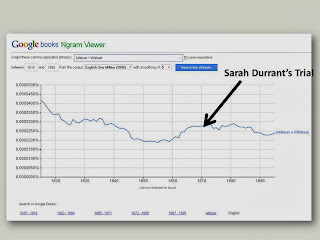

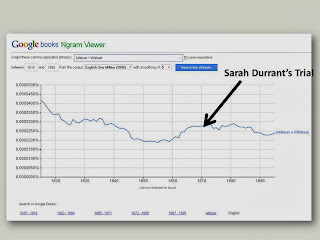

And as with Magnus Huber’s Corpus mark-up, using that linguistic reading of an individual trial as a whole, in relation to Google Books, we could both identify the words that make this trial distinctive, and start the process of contextualising them. We could worry, for instance, at the fact that the trial includes a very early appearance of a 'Detective' giving evidence, and suggesting that Sarah’s experience was unusual and new - providing a different reading again:

In other words, our ability to do a bit of close reading - of lives, of people, of happenstance, and text, with a bit of context thrown in, has become much deeper than it was fifteen years ago.

But we can go further still. We could contextualise Sarah's experience among that of some 240,000 defendants like her, brought to trial over 239 years at the Old Bailey, and reported in 197,475 different accounts. We can visualise these trials by length, and code them for murder and manslaughter, or we could just as easily do it by verdict, or gender, punishment, or crime location. The following material is the outcome of a joint research project with William Turkel at the University of Western Ontario.

Sarah Durrant is here:

And in the process we can locate her experience in relation to the rise of ‘plea bargaining’ and the evolution of a new bureaucracy of judgement and punishment, as evidenced here:

Sarah’s case stood in the middle of a period during which, for the first time, large numbers of trials were being determined in negotiation with the police and the legal profession – all back-rooms and truncheons – resulting in a whole new slew of trials that were reported in just a few words. Read in conjunction with the unusual appearance of a ‘detective’ in the text, and her own use of the language of her youth, the character of her experience becomes subtly different, subtly shaded.

To put this differently, one of the most interesting things we can know about Sarah, is that she was confronted by a new system of policing, and a new system of trial and punishment, which her own language somehow suggests she would have found strange and hard to navigate. We also know that she was desperate to enter a plea bargain. "I know I have done wrong; but don't take me ... [to the station], or I shall get ten years"— pleading to be let go, in exchange for the two bank notes.

And in the end, it was the court's choice to refuse Durrant's plea for a bargain:

"THE COURT would not withdraw the case from the Jury, and stated, the case depended entirely upon the value of the things stolen. GUILTY of receiving— Two Years' Imprisonment."

In other words, Sarah’s case exemplifies the implementation of a new system of justice in which the state – the police and the court – took to themselves a new power to impose its will on the individual. And, it also exemplifies the difficulty that many people – both the poor and the old – must have had in knowing how to navigate that knew system.

But it also places her in a new system designed to ensure an ever more certain and rising conviction rate. And of course, we can see Sarah’s place in that story as well:

Even without the plea bargain, Sarah’s conviction was almost certain – coming as it did in a period during which a higher proportion of defendants were found guilty than at almost any other time before or since. Modern British felony conviction rates are in the mid-70 percent range.

Or alternatively, we can go back to the trial text and use it to locate similar trials – ‘More like this’ – using a TF-IDF – text frequency/inverse document frequency methodology, to find the ten or hundred most similar trials.

In fact these seem to be noteworthy mainly for the appearance of bank-notes and female defendants, and the average length of the trials – none, for instance, can be found among the shorter plea bargains trials at the bottom of the graph, and instead are scattered across the upper reaches, and are restricted to the second half of the nineteenth century - sitting amongst the trials involving the theft of 'bank notes'; and theft more generally, which were themselves, much more likely than crimes of violence, to result in a guilty verdict. At a time when the theft resulted in a conviction rates of between 78% and 82%; killings had a conviction rate of between 41% and 57%.

In other words, applying TF-IDF methodologies provides a kind of bridge between the close and distant readings of Sarah's trial.

And of course, while I don’t do topic modelling, you could equally apply this technique to the text, by simply thinking of the trials as ‘topics’; and I suspect you would find similar results.

But we can read it in other ways as well. We can measure, for instance, whether the trial text has a consistent relationship with the trial outcome - did the evidence naturally lead to the verdict? This work is the result of a collaboration between myself and Simon DeDeo and Sara Klingenstein at the Santa Fe Institute (see Dedeo, et al, 'Bootstrap Methods for the Empirical Study of Decision-Making and Information Flows in Social Systems', for a reflection of one aspect of this work). And in fact, trial texts by the 1870s did not have a consistent relationship to verdicts - probably reflecting again the extent to which legal negotiations were increasingly being entered in to outside the courtroom itself, in police cells, and judge’s chambers - meaning the trials themselves become less useful as a description of the bureaucratic process:

Or, coming out of the same collaboration, we can look to alternative measures of the semantic content of each trial - in this instance, a measure of the changing location of violent language. This analysis is based on a form of ‘explicit semantics’, using the categories of Roget’s thesaurus to group words by meaning. Durrant's trial was significantly, but typically, for 1871, unencumbered with the language of violence. Whereas, seventy years earlier, it would as equally, be likely to contain descriptions of violence – even though it was a trial for that most white collar of crimes, receiving.

In other words, the creation of new tools and bodies of data, have allowed us to 'read' this simple text and the underlying bureaucratic event that brought it into existence, and arguably some of the social experience of a single individual, in a series of new ways. We can do ‘distant reading’, and see this trial account in the context of 127 million words - or indeed the billions of words in Google Books; and we can do a close reading, seeing Sarah herself in her geographical and social context.

In this instance, each of these readings, seems to reinforce a larger story about the evolution of the court, of a life, of a place - a story about the rise of the bureaucracy of the modern state, and of criminal justice. But it was largely by starting from a picture, a face, a stair of fear, that the story emerged.

But the point is wider than this. Reading text – close, distant, computationally, or immersively - is the vanilla sex of the digital humanities and digital history. It is all about what might be characterised as the 'textual humanities'. And for all the fact that we have mapped and photographed her, Sarah remains most fully represented in the text of her trial. But, if you want something with a bit more flavour we need to move beyond what was deliberately coded to text – or photographs – and be more adventurous in what we are reading.

In performance art, in geography and archaeology, in music and linguistics, new forms of reading are emerging with each passing year that seem to significantly challenge our sense of the ‘object of study’. In part, this is simply a reflection of the fact that all our senses and measures are suddenly open to new forms of analysis and representation - when everything is digital, everything can be read in a new way.

Consider for a moment:

This is the ‘LIVE’ project from the Royal Veterinary College in London, and their ‘Haptic Interface’. In this instance they have developed a full scale ‘haptic’ representation of a cow in labour, facing a difficult birth, which allows students to physically engage and experience the process of manipulating a calf in situ. I haven’t had a chance to try this, but I am told that it is a mind altering experience. But for the purpose of understanding Sarah’s world, it also presents the possibility of holding the banknotes, of diving surreptitiously into the briefcase, of feeling the damp wall of her cell, and the worn wooden rail of the bar at the court. It suggests that reading can be different; and should include the haptic - the feel and heft of a thing in your hand. This is being coded for millions of objects through 3d scanning; but we do not yet have an effective way of incorporating that 3d text in to how we read the past.

The same could be said of the aural - that weird world of sound on which we continually impose the order of language, music and meaning; but which is in fact a stream of sensations filtered through place and culture.

Projects like the Virtual St Paul's Cross, which allows you to ‘hear’ John Donne’s sermons from the 1620s, from different vantage points around the square, changes how we imagine them, and moves from ‘text’ to something much more complex, and powerful. And begins to navigate that normally unbridgeable space between text and the material world.

For Sarah, my part of a larger project to digitise andlink the records of nineteenth-century criminal transportation and imprisonment, is to create a soundscape of the courtroom where Sarah was condemned; and to re-create the aural experience of the defendant - what it felt like to speak to power, and what it felt like to have power spoken at you from the bench. And in turn, to use that knowledge, to assess who was more effective in their dealings with the court, and whether, having a bit of shirt to you, for instance, effected your experience of transportation or imprisonment.

All of which is to state the obvious. There are lots of new readings that change how we connect with historical evidence – whether that is text, or something more interesting. In creating new digital forms of inherited culture - the stuff of the dead - we naturally innovate, and naturally enough, discover ever changing readings.

And in the process it feels that we are slowly creating an environment like Katy Börner's notion of a Macroscope - that set of tools, and digital architecture, that allows us to see small and large, at one and the same time; to see Sarah Durrant's moles, while looking at 127 million words of text.

But, before I descend in to that somewhat irritating, Digital Humanities cliché where every development is greeted as both revolutionary, and life enhancing - before I become a fully paid up techno-utopian, I did want to suggest that perhaps all of these developments still leave us with the problem I started with - that the technology is defining the questions we ask. And it is precisely here, that I start to worry at the second half of my title: the 'conundrums of positivism'.

About four years ago - in 2009 or so, I was confronted by something I had not expected. At that time, Bob Shoemaker and I had been working on digitising trial records and eighteenth-century manuscripts for the Old Bailey and London Lives projects for about ten years. In the Old Bailey we had some 127 million words of accurately transcribed text and in the London Lives site, we had 240,000 pages of manuscript materials reflecting the administration of poverty and crime in eighteenth-century London - all transcribed and marked up for re-use and abuse by a wider community of scholars. It all felt pretty cool to me.

But for all the joys of discovery and search digitisation made possible, and the joys of representing the underlying data statistically; none of it had really changed my basic approach to historical scholarship. I kept on doing what I had always done - which basically involved reading a bunch of stuff, tracing a bunch of people and decisions across the archives of eighteenth-century London, and using the resulting knowledge to essentially commentate on the wider historiography of the place and period. My work was made easier, the publications more fully evidenced, and new links and associations were created, that did substantially change how one might look at communities and agency. But, intellectually, digitisation, the digital humanities, did not feel different to me, than had the history writing of twenty years before – to that point, I found myself remarkable un-surprised. But then something happened.

About that time, Google Earth was beginning to impact on geography. With its light, browser based approach to GIS, it had allowed a number of people to create some powerful new sites. Just in my own small intellectual backyard, people like Richard Rogers and a team of collaborators out the National Library of Scotland, were building sites that allowed historical maps to be manipulated, and populated with statistical evidence, online, and in a relatively intuitive Google maps interface. And this was complemented by others, such as the New York Public Library warping site.

It was an obvious thing to want to do something similar for London. And it was a desire to recreate something like this, that led to the Locating London's Past, a screenshot of which I have used already a couple of times. The site used a warped and rectified version of John Rocque's 1746 map of London, in association with the first 'accurate' OS map of the same area, all tied up in a Google Maps container, to map 32,000 place names, and 40,000 trials, and a bunch of other stuff.

But this was where I had my comeuppance. Because in making this project happen, I found myself working with Peter Rauxloh at the Museum of London Archaeological Service, and several of his colleagues - all archaeologists of one sort or another. And from the moment we sat down at the first project meeting, I realised that I was confronted with something that fundamentally challenged my every assumption about history and the past. What shocked me was that they actually believed it.

Up till then it had been a foundational belief of my own, that while we can know and touch the leavings of the dead, the relationship between a past 'reality' and our understanding of it was essentially unknowable - that while we used the internal consistency of the archive to test our conclusions, and in order to build ever more compelling descriptions and explanations of change - actually, we were studying something that was internally consistent, but detached from a knowable reality. In most cases, we were studying 'text', and text alone - with its at least ambiguous relationship to either the mind of the author (whatever that is), and certainly an ambiguous relationship to the world the author inhabited.

Confronted by people happy to define a point on the earth's surface as three simple numbers, and to claim that it was always so, was a shock. This is not to say that the archaeologists were being naïve, far from it, but that having been trained up as a text historian - essentially a textual critic - in those meetings I came face to face with the existence of a different kind of knowing. And, of course, this was also about the time that 'culturomics' was gaining extensive international attention; with its claim to be able to 'read' history from large scale textual change, and to create a 'scientific' analysis of the past. Lieberman Aiden and Michel claim that the process of digitisation, has suddenly made the past available for what they themselves describe as 'scientific purposes

In some respects, we have been here before. In the demographic and cliometric history so popular through the 1970s and 80s, extensive data sets were used to explore past societies and human behaviour. The aspirations of that generation of historians were just as ambitious as are those of the creators of culturomics. But, demography and cliometrics started from a detailed model of how societies work, and sought to test that model against the evidence; revising it in light of each new sample and equation.

The difference with most 'big data' approaches and culturomics is that there is no pretence to a model. Instead, their practitioners seek to discover patterns in the entrails of human leavings hoping to find the inherent meanings encoded there. What I think the scientific community - and quite frankly most historians - finds so compelling is that like quantitative biology and DNA analysis, big data is using one of the controlling metaphors of 20th-century science, 'code breaking' and applying it to a field that has hitherto resisted the siren call of analytical positivism.

Since the 1940s the notion that 'codes' can be cracked to reveal a new understanding of 'nature' has formed the main narrative of science. With the re-description of DNA as just one more code in the 1950s, wartime computer science became a peacetime biological frontier. In other words, what both textual ‘big data’, and the spatial turn, bring to the table is a different set of understandings about the relationship between the historical 'object of study', and a knowable human history; all expressed in the metaphor of the moment - code.

We can all agree that text and objects and landscape form the stuff of historical scholarship, and I suspect that none of us would want to put an exclusionary boundary around that body of stuff. But simply because the results of big data analysis are represented in the grammar of maths (and in 'shock and awe' graphics); or in hyper-precise locations referenced against the modern earth's surface, there is an assumption about the character of the 'truth' the data gives us access to. One need look no further than the use of 'power law' distributions - and the belief that their emergence from raw data reflects an inherently 'natural' phenomenon - to begin to understand how fundamentally at odds traditional forms of historical analysis - certainly in the humanities - is from the emerging 'scientific' histories associated with 'big data'.

But, it is not really my purpose to criticise either the Culturomics team, or archaeologists and geographers (who are themselves engaged in their own form of auto-critique). Rather I just want to emphasise that in choosing to move towards a 'big data' approach - new ways of reading the past - and in adopting the forms of representation and analysis that come with big data, all of us are naturally being pushed subtly towards a kind of social science, and a kind of positivism, which has been profoundly out of favour for at least the last thirty years.

In other words, there seems to me to be a real tension between the desire on the one hand to include the 'reading' of a whole new variety of data in to the process of writing history; and, on the other, the extent to which each attempt to do so, tends to bring to the fore a form of understanding that is at odds with much of the scholarship of the last forty years. We are in danger of giving ourselves over to what sociologists refer to as 'problem closure' - the tendency to reinvent the problem to pose questions that available tools and data allow us to answer - or in Lewis Mumfords words, ask questions we know that computers can answer.

It feels to me as if our practise as humanists and historians is being driven by the technology, rather than being served by it. And really, the issue is that while we have a strong theoretical base from which to critique the close reading of text - we know how complex text is - we do not have the same theoretical framework within which to understand how to read a space, a place, an object, or the inside of a pregnant cow - all suddenly mediated and brought together by code - or to critique the reading of text at a distance. And as importantly, even if there are bodies of theory directed individually at each of these different forms of stuff (and there are); we certainly do not have a theoretical framework of the sort that would allow us to relate our analysis of the haptic, with the textual, the aural and the geographical. Having built our theory on the sands of textuality, we need to re-invent it for the seas of data.

But to come to some kind of conclusion: history is not the past, it is a genre constructed by us from practises first delineated during the enlightenment. Its forms of textual criticism, its claims to authority, its literary conventions, the professional edifice which sifts and judges the product; its very nature and relationship with a reading and thinking public; its engagement with memory and policy, literature and imagination, are ours to make and remake as seems most useful.

For myself, I will read anew, and use all the tools of big data, of ngrams and power laws; and I will publish the results with graphs, tables and GIS; but I refuse to forget that my object of study, my objective, is an emotional, imaginative and empathetic engagement with Sarah Durrant, and all the people like her.

This talk forms a quiet reflection on how the creation of new digital resources has changed the ways in which we read the past; and an attempt to worry at the substantial impact it is having on the project of the humanities and history more broadly. In the process it asks if the collapse of the boundaries between types of data - inherent in the creation of digital simulcra - is not also challenging us to rethink the 'humanities' and all the sub-disciplines of which it is comprised. I really just want to ask, if new readings have resulted in new thinking? And if so, whether that new thinking is of the sort we actually want?

As Lewis Mumford suggested some fifty years ago, most of the time:

‘… minds unduly fascinated by computers carefully confine themselves to asking only the kind of question that computers can answer...’

Lewis Mumford, “The Sky Line "Mother Jacobs Home Remedies",” The New Yorker, December 1, 1962, p. 148.

But, it seems to me that we can do better than that, but that in the process we need to think a bit harder than we have about the nature of the Digital History project.

Perhaps the obvious starting point is with the concept of the distant reading of text, and that wonderful sense that millions of words can be consumed in a single gulp. Emerging largely from literary studies, and in the work of Franco Moretti and Stephen Ramsay, the sense that text – or at least literature – can be usefully re-read with the tools of the digital humanities has been regularly re-stated with the all the hyperbole for which the Digital Humanities is so well known. And, within reason, that hyperbole is justified.

My favourite example of this approach is Ben Schmidt’s analysis of the dialogue in Mad Men, in which he compares the language deployed by the scriptwriters against the corpus of text published in that particular year drawn from Google books. In the process he illustrates that early episodes over-state the ‘performative’ character of the language, particularly in relation to masculinity – that the scriptwriters chose to depict male characters talking about the outside world and objects, more frequently than did the writers of the early fifties. And that in the later episodes of the series, they depict male characters over-using words associated with interiority, emotions and personal perceptions. What I like about this is that it forms one of the first times I have been really surprised by ‘distant reading’. I just had not clocked that the series was developing a theme along these lines – that it embedded a story of the evolution of masculinity from a performative to an interiorised variety. But once Schmidt used a form of distant reading to expose the transition it felt right, obvious and insightful. In Schmidt’s words: ‘the show's departures from the past… let us see just how much everything has changed, even more than its successes.’… at mimicking past language. The same could be done with the works of George Elliot or Tolstoy (who both wrote essentially ‘historical’ novels), and with them too, I look forward to being surprised. In other words, the existence of something like Google Books and the Ngram viewer - which Schmidt's work depends upon - actually can change the character of how we ‘read’ a sentence, a word, a phrase, a genre – by giving a norm against which to compare it. Is it a ‘normal’ word, for the date? or more challenging, for the genre? for the place of publication? for the word's place in the long string of words that make up an article or a book?

But having lauded this example, I think we also have to admit that in most stabs at distant reading seems to tell us what we already know.

There was an industrial revolution involving iron. There was a war in the 1860s and so on.

What surprises me most, is that I am not more surprised.

In part, I suspect the banal character of most ngrams and network analyses is a reflection of the extent to which books, indexes, and text, have themselves been a very effective technology for thinking about words. And that as long as we are using digital technology to re-examine text, we are going to have a hard time competing with two hundred years of library science, and humanist enquiry. Our questions are still largely determined by the technology of books and library science, so it is little wonder that our answers look like those found through an older techonology.

But, the further we move away from either the narrow literary cannon; and more importantly the code that is text, to include other types of readings of other types of data - sound, objects, spaces - I hope the more unusual and surprising our readings – both close and distant - might become. And it is not just text and objects, but also cultures. The current collection of digital material that forms the basis for most of our research is composed of the maudlin leavings of rich dead white men (and some rich dead white women). Until we get around to including the non-cannonical, the non-Western, the non-textual and the non-elite, we are unlikely to be very surprised.

For myself, I am wondering how we might relate non-text to text more effectively; and how we might combine - for historical purposes - close and distant reading into a single intellectual practise; how we might identify new objects of study, rather than applying new methodologies to the same old bunch of stuff. And just by way of a personal starting point, I want to introduce Sarah Durrant. She is not important. Her experience does not change anything, but she does provide a slightly different starting point from all the rich dead white men. And for me, she represents a different way of thinking through how to ask questions of computers, without simply asking questions we know computers can answer.

Sarah claimed to have found two bank notes on the floor of the coffee house she ran in the London Road, on the Whitsun Tuesday, 1871; at which point she pocketed them. In fact they had been lifted from the briefcase of Sydney Tomlin, in the entrance way of the Birkbeck Bank, Chancery Lane, a few days earlier.

We know what Sarah looked like. This image is part of the record of her imprisonment at Wandsworth Gaol for two years at hard labour, and is readily available through the website of the UK's National Archives. We have her image, her details, her widowed status, the existence of two moles - one on her nose and the other on her chin. We have her scared and resentful eyes staring at us from a mug shot. I don't have the skill to interpret this representation in the context of the history of portraiture, or the history of photography - but it creates a powerful if under-theorised alternative starting point from which to read text - and has the great advantage of not being ‘text’; or at least not being words.

But, we also have the words recorded in her trial.

And because we have marked up this material to within an inch of their life in XML to create layer upon layer of associated data, we also have something more.

In other words, for Sarah, we can locate her words, and her image, her imprisonment and experience, both in ‘text’ and in the leavings of the administration of a trial, as marked up in the XML. And because we have studiously been giving this stuff away for a decade, there is a further ‘reading’ that is possible, via an additional layer of XML provided by Magnus Huber and his team at the University of Giessen. He has marked up all the text that purports to encompass a ‘speech act’. And so we also have a further ‘reading’ of Sarah as a speaker, and not just any speaker, but a working class female speaker in her 60s.

And of course, this allows us to compare what she says, to other women of the same age and class, using the same words; with a bit of context for the usage.

So, we already have a few ‘readings’, including text, bureaucratic process, and purported speech.

From all of which we know that Sarah, moles and all, was convicted of receiving; and that she had been turned in by a Mrs Seyfert - a drunk, who Durrant had refused a hand-out. And we know that she thought of her days in relation to the Anglican calendar, which by 1871, was becoming less and less usual – and reflects the language of her childhood.

And, of course, we have an image of the original page on which that report was published – a ghost of the material leavings of an administrative process.

And just in case, we can also read the newspaper report of the same trial.

So far, so much text, with a couple of layers of XML, and the odd image. But we also know who was in Wandsworth Gaol with her on the census day in 1871.

And we know where Durrant had been living when the crime took place – in Southwark, at No 1 London Road.

We know that she was a little uncertain about her age, and we know who lived up one flight of stairs, and down another. Almost randomly, we can now know an awful lot about most nineteenth century Londoners, allowing us to undertake a new kind of 'close reading'.

From which it is a small step to The Booth Archive site posted by the London School of Economics, which in turn lets us know a bit more about the street and its residents.

‘a busy shopping street', with the social class of the residents declining sharply to the West - coded Red for lower middle class.

But we can still do a bit better than this. We can also do what linguists and literary scholars are doing to their own objects of study - we can take apart the trial, for instance, as a form of generic text using facilities such as Voyant Tools. Turning a ‘historical reading’ in to a linguistic one:

And, if the OCR of the Times Digital Archive was sufficiently good (which it isn’t) - we could have compared the trial account, with the newspaper account as a measurable body of text.

And as with Magnus Huber’s Corpus mark-up, using that linguistic reading of an individual trial as a whole, in relation to Google Books, we could both identify the words that make this trial distinctive, and start the process of contextualising them. We could worry, for instance, at the fact that the trial includes a very early appearance of a 'Detective' giving evidence, and suggesting that Sarah’s experience was unusual and new - providing a different reading again:

In other words, our ability to do a bit of close reading - of lives, of people, of happenstance, and text, with a bit of context thrown in, has become much deeper than it was fifteen years ago.

But we can go further still. We could contextualise Sarah's experience among that of some 240,000 defendants like her, brought to trial over 239 years at the Old Bailey, and reported in 197,475 different accounts. We can visualise these trials by length, and code them for murder and manslaughter, or we could just as easily do it by verdict, or gender, punishment, or crime location. The following material is the outcome of a joint research project with William Turkel at the University of Western Ontario.

Sarah Durrant is here:

And in the process we can locate her experience in relation to the rise of ‘plea bargaining’ and the evolution of a new bureaucracy of judgement and punishment, as evidenced here:

Sarah’s case stood in the middle of a period during which, for the first time, large numbers of trials were being determined in negotiation with the police and the legal profession – all back-rooms and truncheons – resulting in a whole new slew of trials that were reported in just a few words. Read in conjunction with the unusual appearance of a ‘detective’ in the text, and her own use of the language of her youth, the character of her experience becomes subtly different, subtly shaded.

To put this differently, one of the most interesting things we can know about Sarah, is that she was confronted by a new system of policing, and a new system of trial and punishment, which her own language somehow suggests she would have found strange and hard to navigate. We also know that she was desperate to enter a plea bargain. "I know I have done wrong; but don't take me ... [to the station], or I shall get ten years"— pleading to be let go, in exchange for the two bank notes.

And in the end, it was the court's choice to refuse Durrant's plea for a bargain:

"THE COURT would not withdraw the case from the Jury, and stated, the case depended entirely upon the value of the things stolen. GUILTY of receiving— Two Years' Imprisonment."

In other words, Sarah’s case exemplifies the implementation of a new system of justice in which the state – the police and the court – took to themselves a new power to impose its will on the individual. And, it also exemplifies the difficulty that many people – both the poor and the old – must have had in knowing how to navigate that knew system.

But it also places her in a new system designed to ensure an ever more certain and rising conviction rate. And of course, we can see Sarah’s place in that story as well:

Even without the plea bargain, Sarah’s conviction was almost certain – coming as it did in a period during which a higher proportion of defendants were found guilty than at almost any other time before or since. Modern British felony conviction rates are in the mid-70 percent range.

Or alternatively, we can go back to the trial text and use it to locate similar trials – ‘More like this’ – using a TF-IDF – text frequency/inverse document frequency methodology, to find the ten or hundred most similar trials.

In fact these seem to be noteworthy mainly for the appearance of bank-notes and female defendants, and the average length of the trials – none, for instance, can be found among the shorter plea bargains trials at the bottom of the graph, and instead are scattered across the upper reaches, and are restricted to the second half of the nineteenth century - sitting amongst the trials involving the theft of 'bank notes'; and theft more generally, which were themselves, much more likely than crimes of violence, to result in a guilty verdict. At a time when the theft resulted in a conviction rates of between 78% and 82%; killings had a conviction rate of between 41% and 57%.

In other words, applying TF-IDF methodologies provides a kind of bridge between the close and distant readings of Sarah's trial.

And of course, while I don’t do topic modelling, you could equally apply this technique to the text, by simply thinking of the trials as ‘topics’; and I suspect you would find similar results.

But we can read it in other ways as well. We can measure, for instance, whether the trial text has a consistent relationship with the trial outcome - did the evidence naturally lead to the verdict? This work is the result of a collaboration between myself and Simon DeDeo and Sara Klingenstein at the Santa Fe Institute (see Dedeo, et al, 'Bootstrap Methods for the Empirical Study of Decision-Making and Information Flows in Social Systems', for a reflection of one aspect of this work). And in fact, trial texts by the 1870s did not have a consistent relationship to verdicts - probably reflecting again the extent to which legal negotiations were increasingly being entered in to outside the courtroom itself, in police cells, and judge’s chambers - meaning the trials themselves become less useful as a description of the bureaucratic process:

Or, coming out of the same collaboration, we can look to alternative measures of the semantic content of each trial - in this instance, a measure of the changing location of violent language. This analysis is based on a form of ‘explicit semantics’, using the categories of Roget’s thesaurus to group words by meaning. Durrant's trial was significantly, but typically, for 1871, unencumbered with the language of violence. Whereas, seventy years earlier, it would as equally, be likely to contain descriptions of violence – even though it was a trial for that most white collar of crimes, receiving.

In other words, the creation of new tools and bodies of data, have allowed us to 'read' this simple text and the underlying bureaucratic event that brought it into existence, and arguably some of the social experience of a single individual, in a series of new ways. We can do ‘distant reading’, and see this trial account in the context of 127 million words - or indeed the billions of words in Google Books; and we can do a close reading, seeing Sarah herself in her geographical and social context.

In this instance, each of these readings, seems to reinforce a larger story about the evolution of the court, of a life, of a place - a story about the rise of the bureaucracy of the modern state, and of criminal justice. But it was largely by starting from a picture, a face, a stair of fear, that the story emerged.

But the point is wider than this. Reading text – close, distant, computationally, or immersively - is the vanilla sex of the digital humanities and digital history. It is all about what might be characterised as the 'textual humanities'. And for all the fact that we have mapped and photographed her, Sarah remains most fully represented in the text of her trial. But, if you want something with a bit more flavour we need to move beyond what was deliberately coded to text – or photographs – and be more adventurous in what we are reading.

In performance art, in geography and archaeology, in music and linguistics, new forms of reading are emerging with each passing year that seem to significantly challenge our sense of the ‘object of study’. In part, this is simply a reflection of the fact that all our senses and measures are suddenly open to new forms of analysis and representation - when everything is digital, everything can be read in a new way.

Consider for a moment:

This is the ‘LIVE’ project from the Royal Veterinary College in London, and their ‘Haptic Interface’. In this instance they have developed a full scale ‘haptic’ representation of a cow in labour, facing a difficult birth, which allows students to physically engage and experience the process of manipulating a calf in situ. I haven’t had a chance to try this, but I am told that it is a mind altering experience. But for the purpose of understanding Sarah’s world, it also presents the possibility of holding the banknotes, of diving surreptitiously into the briefcase, of feeling the damp wall of her cell, and the worn wooden rail of the bar at the court. It suggests that reading can be different; and should include the haptic - the feel and heft of a thing in your hand. This is being coded for millions of objects through 3d scanning; but we do not yet have an effective way of incorporating that 3d text in to how we read the past.

The same could be said of the aural - that weird world of sound on which we continually impose the order of language, music and meaning; but which is in fact a stream of sensations filtered through place and culture.

Projects like the Virtual St Paul's Cross, which allows you to ‘hear’ John Donne’s sermons from the 1620s, from different vantage points around the square, changes how we imagine them, and moves from ‘text’ to something much more complex, and powerful. And begins to navigate that normally unbridgeable space between text and the material world.

For Sarah, my part of a larger project to digitise andlink the records of nineteenth-century criminal transportation and imprisonment, is to create a soundscape of the courtroom where Sarah was condemned; and to re-create the aural experience of the defendant - what it felt like to speak to power, and what it felt like to have power spoken at you from the bench. And in turn, to use that knowledge, to assess who was more effective in their dealings with the court, and whether, having a bit of shirt to you, for instance, effected your experience of transportation or imprisonment.

All of which is to state the obvious. There are lots of new readings that change how we connect with historical evidence – whether that is text, or something more interesting. In creating new digital forms of inherited culture - the stuff of the dead - we naturally innovate, and naturally enough, discover ever changing readings.

And in the process it feels that we are slowly creating an environment like Katy Börner's notion of a Macroscope - that set of tools, and digital architecture, that allows us to see small and large, at one and the same time; to see Sarah Durrant's moles, while looking at 127 million words of text.

But, before I descend in to that somewhat irritating, Digital Humanities cliché where every development is greeted as both revolutionary, and life enhancing - before I become a fully paid up techno-utopian, I did want to suggest that perhaps all of these developments still leave us with the problem I started with - that the technology is defining the questions we ask. And it is precisely here, that I start to worry at the second half of my title: the 'conundrums of positivism'.

About four years ago - in 2009 or so, I was confronted by something I had not expected. At that time, Bob Shoemaker and I had been working on digitising trial records and eighteenth-century manuscripts for the Old Bailey and London Lives projects for about ten years. In the Old Bailey we had some 127 million words of accurately transcribed text and in the London Lives site, we had 240,000 pages of manuscript materials reflecting the administration of poverty and crime in eighteenth-century London - all transcribed and marked up for re-use and abuse by a wider community of scholars. It all felt pretty cool to me.

But for all the joys of discovery and search digitisation made possible, and the joys of representing the underlying data statistically; none of it had really changed my basic approach to historical scholarship. I kept on doing what I had always done - which basically involved reading a bunch of stuff, tracing a bunch of people and decisions across the archives of eighteenth-century London, and using the resulting knowledge to essentially commentate on the wider historiography of the place and period. My work was made easier, the publications more fully evidenced, and new links and associations were created, that did substantially change how one might look at communities and agency. But, intellectually, digitisation, the digital humanities, did not feel different to me, than had the history writing of twenty years before – to that point, I found myself remarkable un-surprised. But then something happened.

About that time, Google Earth was beginning to impact on geography. With its light, browser based approach to GIS, it had allowed a number of people to create some powerful new sites. Just in my own small intellectual backyard, people like Richard Rogers and a team of collaborators out the National Library of Scotland, were building sites that allowed historical maps to be manipulated, and populated with statistical evidence, online, and in a relatively intuitive Google maps interface. And this was complemented by others, such as the New York Public Library warping site.

It was an obvious thing to want to do something similar for London. And it was a desire to recreate something like this, that led to the Locating London's Past, a screenshot of which I have used already a couple of times. The site used a warped and rectified version of John Rocque's 1746 map of London, in association with the first 'accurate' OS map of the same area, all tied up in a Google Maps container, to map 32,000 place names, and 40,000 trials, and a bunch of other stuff.

But this was where I had my comeuppance. Because in making this project happen, I found myself working with Peter Rauxloh at the Museum of London Archaeological Service, and several of his colleagues - all archaeologists of one sort or another. And from the moment we sat down at the first project meeting, I realised that I was confronted with something that fundamentally challenged my every assumption about history and the past. What shocked me was that they actually believed it.