The post that follows is formed from the text of a presentation I am due to deliver at King's College London on 9 February, but which reflects what I was worrying about in early December 2011 - several months after I wrote the synopsis that was used to advertise the talk, a month before I attended the AHA conference in Chicago with its extensive programme on digital histories, and six weeks before I got around to reading Stephen Ramsay's, Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism. Both listening to the text mining presentations at the AHA, and thinking about Ramsay's observations about computers and literary criticism have contributed to moving me on from the text below. In particular, Ramsay's work has encouraged me to remember that history writing has always been more fully conceived by its practitioners as an act of 'creation', and as a craft in its own right, than has literary criticism (which has more fully defined itself against a definable 'other' - a literary object of study). As a result, I found myself fully in agreement with Ramsay's proposal that digital criticisms should '...channel the heightened objectivity made possible by the machine into the cultivation of those heightened subjectivities necessary for critical work.'(p.x) But was most struck by his conclusion that the 'hacker/scholar' had moved camps from critic to creator. (p.85). It made me remember that even the most politically informed and technically sophisticated piece of digital analysis only becomes 'history' when it is created and consumed as such. This made me reflect that we have the undeniable choice to create new forms of history that retain the empathetic and humane characteristics found in the old generic forms; and simply need to get on with it. In the process I have concluded that the conundrums of positivism with which this post are concerned, are in many ways a canard that detract from crafting purposeful history.

Academic History Writing

and the Headache of Big Data

In the nature of titles and synopses for presentations such as this one, you write them before you write the paper, and they reflect what you are thinking about at the time. My problem is that I keep changing my mind. I try to dress this up as serious open mindedness – a constant engagement with a constantly changing field, but in reality it is just a kind of inexcusable intellectual incontinence – which I am afraid I am going to force you all to witness this afternoon.

I

promised to spend the next forty minutes or so discussing research

methodologies, historical praxis and the challenge of ‘big data’; and I do

promise to get there eventually. But

first I want to do something deeply self-serving and self-indulgent that

nevertheless seemed to me a necessary pre-condition for making any serious

statement about both the issues raised by recent changes in the technical

landscape, and how ‘Big Data’, in particular, will impact on writing history –

and whether this is a good thing.

And

I am afraid, the place I need to start is with some thirteen years spent

developing online historical resources.

Unlike

a lot of people working in the digital humanities, in collaboration with Bob

Shoemaker, I have pretty much controlled my research agenda and the character

of the projects I have worked on from day one.

This has been a huge privilege for which I am hugely grateful, but it

means that there has been an underlying trajectory embedded within my work as a

historian and digital humanist. This agenda has been continuously negotiated with Bob Shoemaker, whose own distinct agenda and perspective has also fundamentally shaped the resulting projects, and more recently with Sharon Howard; and has been informed throughout by the work of Jamie McLaughlin who has been primarily responsible for the programming involved. But, the websites I have helped to

create were designed with our historical

interests and intellectual commitments as imperatives.

And as such they incorporate a series of explicit assumptions that have worked

in dialogue with the changing technology.

In other words, the seven or eight major projects I have co-directed are, from my perspective at least, fragments of a single coherent research agenda and project.

And

that project is about the amalgamation of the Digital Humanities with an

absolute commitment to a particular kind of history: ‘History from Below’. They form an attempt to integrate the British

Marxist Historical Tradition, with all the assumptions that implies about the

roles of history in popular memory, and community engagement, with digital delivery. In the language of the moment, they are a

fragment of what we might discuss as a peculiar flavour of ‘public history’. And what I feel I have discovered in the last

five or six years, is that there is a fundamental contradiction between the

direction of technological development, and that agenda – that ‘big data’ in

particular, and history from below don’t mix.

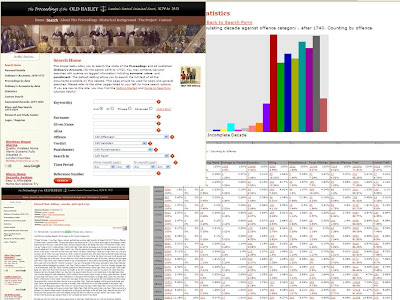

We

started with the Old Bailey Proceedings

– not because it was a perfect candidate for digitisation (who knew what that

looked like in 1999), but because it was the classic source for ‘history from

below’ and the social history of eighteenth-century London, used by Edward

Thompson and George Rude.

·

- 125 million words of trial accounts

- 197,745 trials reflecting the brutal exercise of state power on the relatively powerless.

- 250,000 defendants, and 220,000 victims.

A

constant and ever changing litmus test of class and social change.

The

underlying argument – in 1999 – was that the web represented a new public face

for historical analysis, and that by posting the Old Bailey Proceedings we empowered everyone to be their own

historian – to discover for themselves that landscape of unequal power. By 2003, when we posted the first iteration

of the site – and more as a result of the creation of the online census’s rather

the Old Bailey itself – the argument had changed somewhat to a simple

acceptance of the worth and value of a demonstrable democratisation of access

to the stuff of social history.

The

site did not have the explicit political content of Raphael Samuel’s work or

Edward Thompson’s, but it both created an emphasis on the lived experience of

the poor, and gave free public access to the raw materials of history to what

are now some 23 million users.

And

it is important to remember at this point what most academic projects have

looked like for the last decade, and the kinds of agendas that underpin

them. If you wanted to characterise the

average academic historical web resource, it would be a digitisation project

aimed at the manuscripts of a philosopher or ‘scientist’. Newton, Bentham, the Philosophes, or founding

fathers in the US; most digital projects have replicated the intellectual, and

arguably rather intellectually old fashioned end, of the broader historical

project. Gender history, the radical

tradition, even economic and demographic history have been poorly represented

on line – despite the low technical hurdles involved in posting the evidence

for demographic and economic history in particular.

The

importance of the Old Bailey therefore was simply to grab an audience for the

kind of history that I wanted people to be thinking about – empathetic, aware

of social division and class, and focused on non-elite people. And to do so as a balance to what increasingly

seems to me to be the emergence of a very conservative notion of what

historical material looked like.

The

next step – the creation of the London

Lives web site, was essentially driven by the same agenda, with the

explicit addition that it should harness that wild community of family

historians, and wild interest in the history of the individual, to creating an

understanding of individuals in their specific contexts – of building lives, by

way of building our understanding of communities, and essentially – of social

relationships.

- 3.5 million names,

- 240,000 pages of transcribed manuscripts reflecting social welfare and crime

- and a framework that allowed individual users to create individual lives, that could in turn be built in to micro-histories.

This

hasn’t garnered quite the same audience, or had the same impact as the Old Bailey Online (it does not contain

the glorious narrative drama inherent in a trial account), and the history it

contains is just harder work to make real.

But,

from my perspective, the character and end of the two projects were absolutely

consistent. Designed around 2004 (and

completed in 2010), in some respects London

Lives was a naïve attempt to make crowd sourcing an integral part of the

process – though not in order to get work done for free (which seems to be the

motivation for applying crowdsourcing in a lot of instances), but more as a way

of helping to create communities of users, who in turn become both communities

of consumers of history, and communities of creators, of their own histories.

Around

the same time as London Lives was

kicking off, starting in 2005, and in collaboration with Mark Greengrass, we

began to experiment with Semantic Web methodologies, Natural Language

Processing, and a bunch of Web 2.0 techniques – all of which were driven in

part by the engagement of people like Jamie McLaughlin, Sharon Howard, Ed

McKenzie and Katherine Rogers at the Humanities Research Institute in Sheffield,

and in part by the interest generated by the Old Bailey as a ‘Massive Text

Object’ from digital humanists such as Bill Turkel. In other words, during the middle of the last

decade, the balance between the technology and its use as a mode of delivery

began to shift. We became more

technically engaged with the Digital Humanities, and this began to create a

tension with the historical agenda we were pursuing.

And

as a result, it was around this point that the basic coherence of the

underlying project became more confused.

Just as the demise of the Arts and Humanities Data Service in 2007 signalled the end of a coherent

British digitisation policy (and the end of a particular vision of how history

online might work), the rising significance of external technical developments

began to impact significantly on our agenda, as we worked to amalgamate rapid technical

innovation with the values and expectations of a public, democratic form of

history. In other words the technology began

to overtake our initial and underlying purpose.

And

the first upshot of that elision was the Connected Histories site:

- 15 Major web resources

- 10 billion words

- 150,000 images

All

made available through a federated search facility. Everything from Parliamentary Papers, to collections of ephemera and the British

Museum’s collection of prints and drawings, were brought together and made

keyword searchable through an abstracted index.

With its distributed API architecture and use of NLP to tag a wide variety

of source types, it represented a serious application of what at the time were

relatively new methodologies.

And

unlike the previous sites, it was effectively driven by a changing national

context, and by technology, and included a range of partners far beyond those involved in previous projects - most significantly Jane Winter and the Institute of Historical Research. In part this

project was driven by a critique of data ‘silos’, but more fundamentally, we saw it as

an answer to the incoherence of the digitisation project as a whole, following

the withdrawal of funding to the AHDS, and the closure of the Arts and Humanities

Research Council’s Resource Enhancement Scheme.

It also formed an answer to the firewalls of privilege that were

increasingly being thrown up around newspapers and other big digital resources

– an important epiphenomenon of Britain’s mixed ecology of web delivery. In

other words, while trying desperately to maintain a democratic model of

intellectual access, we were forced to respond to a rapidly changing techno-cultural

environment.

In

many respects, Connected Histories

was an attempt to design an architecture,

including an integral role for APIs, RDF indexes, and a comprehensive

division between scholarly resources, and front end analytical functionality,

that would keep the work of the previous decade safe from complete irrelevance. At its most powerful we believed the

architecture would allow the underlying data to be curated, logged and

preserved, even as the ‘front end’ grew tired and ridiculous.

Early

attempts to make the project automatic

and fully self-sustaining through the use of crawlers, and hackerish scraping

methodologies fell by the way, as even the great national memory institutions

and commercial operations like ProQuest and Gale, signed up to the project.

But,

we also kept the hope that Connected

Histories would effectively allow democratic access (or at least a

democratically available map of the online landscape) to every internet user. There was no real, popular demand for this. Google has frightened us all in to believing

there is an infinite body of material out there, so we can’t know its full extent. But it seemed important to us that what the

public has paid for should be knowable by the public.

And

here is where the conundrums of ‘Big Data’ begin. And these conundrums are of two sorts – the

first simple and technical; and the second more awkward and philosophical.

By

this time, two years ago or so, we had what looked like ‘pretty big data’, and the outline of a robust technical

architecture that separated out academic

resources from search facilities, both making the data much more sustainable and easily curated, and

the analysis much more challenging and interesting. Suddenly, all the joys of

datamining, corpus linguistics, textmining, of network analysis and interactive

visualisations beckoned.

And

it is this latter challenging and exciting analytical environment that is so

fundamentally problematic. Because we

had ‘pretty big data’, and the architecture to do something serious with it, we

suddenly found ourselves very much in danger of excluding precisely the

audience for history that we started out to address. The intellectual politics of the projects

(the commitment to a history from below), and the technology actually came in

to conflict for the first time – though this would only be apparent if you

looked under the bonnet, at the underlying architecture and the modes of

working it assumed.

One

problem is that these new methodologies are and will continue to be reasonably

technically challenging. If you need to

be command-line comfortable to do good history – there is no way the web

resources created are going to reach a wider democratic audience, or allow them

to create histories that can compete for attention with those created within

the academy – you end up giving over the creation of history to a top down,

technocratic elite. In other words, you

build in ‘history from above’, rather than ‘history from below’, and arguably

privilege conservative versions of the past.

One way forward, therefore, lay in attempting to make this new

architecture work more effectively for an audience without substantial

technical skills.

In collaboration with Matthew Davies and Mark Merry at the Centre for Metropolitan History and with the Museum of London Archaeological Service, we tried to do just this with Locating

London’s Past.

- Seventeen datasets

- 4.9 million geo-referenced place names

- 29,000 individually defined polygons.

But

the main point is that it is a shot at creating the most intuitive front end

version we could imagine of the sort of ‘mash up’ that the API architecture

makes both possible, and effectively encourages.

In

other words, this was an attempt to take what a programmer might want to

achieve with an API, and put it directly into the hands of a wider

non-technical public. And we chose maps

and geography as the exemplar data, and GIS as the best methodology, simply

because, while every geographer will tell you maps are profound ideological

constructs embedding a complex discourse, they are understood by a wider public

in an intuitive and unproblematic way – allowing that public to make use of the

statistics derivable from ‘big data’ in a way that intellectually feels like a

classic ‘mash up’, but which requires little more expertise than navigating between

stations on the London underground.

So

arguably, Locating London’s Past is

in a direct line from the Old Bailey,

and London Lives – seeking to engage

and encourage the same basic audience to use the web to make their own history

– and to do so from below – to create a humane, individualistic, and empathetic

history that contributes to a simple politics of humanism.

But

it is not a complete answer, and the next project highlighted the problem even

more comprehensively. At the same time

as we were working on Connected Histories

and Locating London’s Past, by way of

engaging that history from below audience, making all this stuff safe for a

democratic and universal audience - we were also involved with the first round of

the Digging Into Data Programme, with a project called Data Mining With Criminal Intent.

The Data Mining with Criminal Intent project brought together

three teams of scholars including Dan Cohen and Fred Gibbs from CHNM, and Geoffrey Rockwell and Stefan Sinclair of Voyant Tools, along with Bill Turkel from the University of Western Ontario, and Jamie McLaughlin from the HRI in Sheffield. It was intened to achieve just a few things. First, to

build on that new distributed architecture to illustrate how tools and data in

the humanities might be shared across the net - to embed an API methodology

within a more complex network of distributed sites and tools; and second, to create

an environment in which some ‘big data’ might be made available for use with

the innovative tools created by linguists for textual analysis. And finally to begin to explore what kinds of

new questions, these new tools and architecture would allow us to ask and

answer.

To achieve these ends, we brought onto a single metaphorical page, the Old

Bailey material with the browser based citation management system, Zotero, and Voyant Tools – new tools for working with large numbers of

words.

Much

of this was a simple working out of the API architecture and the implications

inherent in separating data from analysis.

But, it also led me to work with Bill Turkel, using Mathematica to do some macro-analysis of the Old Bailey Proceedings themselves.

One

of the interesting things about this is that simply because we did it so long

ago, rekeying the text instead of using an OCR methodology, the Proceedings are now one of the few big

resources relating to the period before 1840 or so, that is actually much use for text mining. Try creating an RDF triple out of the Burney

Collection’s OCR and you get nothing that can be used as the basis for a

semantic analysis – there is just too much noise. The exact opposite is true of the Proceedings because of their semi-structured

character, highly tagged content, and precise transcription. And at 127 million words, they are just about

big enough to do something sensible. And where Bill and I ended up was with a

basic analysis of trial length and verdict over 240 years, that allowed us to

critique and revise the history of the evolution of the criminal justice

system, and the rise of plea bargaining.

And we came to this conclusion through a methodology that I can only

describe as ‘staring at data’ – looking open-eyed at endless iterations of the

material, cut and sliced in different ways.

It is a methodology that is central to much scientific analysis, and it

is fun.

But

it is also where my conundrum comes in. However

compelling the process is, it does not normally result in the kind of history I

do. It is not ‘history from below’, it

is not humanistic, nor is it very humane.

It can only rarely be done by someone working part time out of interest,

and it does not feed in to ‘public history’ or memory in any obvious

way. The result is powerful, and intellectually

engaging – it is the tools of the digital humanities wielded to create a

compelling story that changes how we understand the past (which is fun); but it

is a contribution to a kind of legal and academic history I do not normally

write.

And

the point is, that the kind of history created in this instance, is precisely

the natural upshot of ‘big data’ analysis.

In other words, what has become self-evident to me, is that ‘big data’,

and even ‘pretty big data’ inevitably creates a different and generically

distinct form of historical analysis, and fundamentally changes the character

of the historical agenda that is otherwise in place. This may seem obvious – but it needs to be stated

explicitly.

To

illustrate this in a slightly different way, we need look no further than the

doyens of ‘big data’; the creators of the Googe Ngram viewer.

I

love the Google ngram

viewer, and it clearly points the way forward in lots of ways. But if you look at what Erez Lieberman Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel

do with it, its impact on the form of historical scholarship begins to look

problematic. Rather like what Bill Turkel

and I did with the Old Bailey material, Lieberman Aiden and Michel appear to

claim to be able to read history from the patterns the ngram viewer exposes -

to decipher significant changes from the data itself. Their usual

examples include the analysis of the decline of irregular verbs to a precise mathematical equation, and the rise of

'celebrity' as measured by the number of times an individual is mentioned in

print.

These

imply that all historical development can, like irregular verbs, be described

in mathematical terms, and that 'human nature', like the desire for fame, can

be used as a constant to measure the changing technologies of culture.

And that like the Old Bailey – we can discover change and effect through

exploring the raw data. And that once we

do this, it will become newly available, in the words of Lieberman Aiden and

Michel, for 'scientific

purposes'.

In

other words, there is a kind of scientific positivism that is actively

encouraged by the model of ‘big data’ analysis.

All the ambiguities of theory and structuralism, thick description and

post modernism are simply irrelevant.

In

some respects, I have no problem with this whatsoever. I have never been a fully paid up

post-modernist, and put most simply, unlike a thorough-going post-modernist, I

think we can know stuff about the past.

I

do, however, have two particular issues. First, if I work towards a more big

data-like approach, I am forced to rework and rethink my own ‘public history’

stance. I am no longer simply making material and empathetic engagement

available to a wider audience; and therefore, the purpose of my labours is left

open to doubt (by myself at the very least).

But second, I am being drawn into a kind of positivism that

assumes what will come out of the equations (the code breaking to use the

dominate metaphor of the last 60 years) is socially usefully or morally

valuable.

In

a sense, what ‘big data’ encourages is a morality-free engagement with a

positivist understanding of human history. In contrast, the core of the historical

tradition has been focused on the dialogue between the present and the past,

and the usefulness of history in creating a working civil society. The lessons we take from the past are those

which we need, rather than those which are most self-evident. If the project of history I bought in to was

politically and morally framed (and it was), the advent of big data challenges

the very root of that project.

Of

course, this should not really be a problem, if only because history has always

been a dialogue between irrefutable evidence, and discursive construction

(between what you find in the archive and what you write in a book). And science and its positivist pretentions

have always been framed within a recognised sociology of knowledge and

constructed hermeneutic.

But,

for me, I remain with a conundrum – how to turn big data in to good

history? How do we preserve the

democratic and accessible character of the web, while using the tools of a

technocratic science model in which popular engagement is generally an

afterthought rather than the point.

I

really just want to conclude about there – with the conundrum. For me, and for most of the digital

humanities in the UK, the journey of the last fifteen years or so has been

about access and audience – issues that are fundamentally un-problematic –

which can be politically engaging and beautiful; and for this, one needs look no

further than Tim Sherratt’s Invisible

Australian’s project.

Even

if you prefer your history in a more elite vein than me, more people being able

to read more sources is an unproblematic good thing, a simple moral good. And arguably, having the opportunity to stare

hard at data, and look for anomalies, and weirdness, is also an unproblematic

good.

But,

if we are now being led by the technology itself to write different kinds of history

– the tools are shaping the product. If

we end up losing the humane and the individual, because the data doesn’t quite

work so easily that way, we are in danger of giving up the power of historical

narrative (the ability to conjure up a person and emotions with words), without

thinking through the nature of what will be gained in exchange. I am tempted to go back to my structuralist /

Marxist roots and start ensuring my questions are sound before the data is

assayed, but this seems to deny the joys of an open-eyed search for the

weird. I am caught between audience and

public engagement, on the one hand, and the positivist implications of big data,

on the other.

And

I am left in a conundrum. In the

synopses I wrote back in October or so, I thought I would be arguing: “that the analysis and exploration

of 'big data' provides an opportunity to re-incorporate historical

understandings in to a positivist analysis, while challenging historians to

engage directly and critically with the tools of computational linguistics.”

The

challenge is certainly there, but I am less clear that the re-integration of

history and positivism can be pursued without losing history’s fundamental and

humanist purpose. For me, there remain

big issues with big data; and a challenge to historians to figure out how to

turn big data, to real historical account.